PRINTER

I Become a Journeyman Printer

Graduation from apprenticeship was truly an

anticlimax — more of a relief than an honor. Each of us had to

make up every hour we had missed from work other than annual and sick

leave, and I had nearly two months of military leave in connection

with my National Guard activities. Others were delayed by various

reasons, so that the graduation came weeks after most of us had

assumed journeyman status. By this time Marion had taken a position

as a secretary in the office of Senator Tom Connally of Texas,

chairman of the Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee, and one

of the most powerful men in Roosevelt’s captive Congress. When

Congress was in session, as it was from January to mid-year or later,

the GPO had a night shift to produce the various documents Congress

generated in its sessions and committee hearings — the

Congressional Record and copies of the original and all amendments to

bills submitted in either house. Since night work paid a 15%

differential, and would give me more freedom in my university work, I

had Marion get me a letter of recommendation from Senator Connally to

have me transferred to the night side. Since the graduation was

scheduled at night, when I would be at work, I wrote a letter to ask

if I should attend as part of my shift time, or should take annual

leave to do so. The Public Printer, Mr. Giegengack, held me up to

ridicule (though he did not name me), as wanting to be paid to

graduate. Work at night may have paid better, but it had its

drawbacks. I was attending day classes at GW, and on some days would

have to go to class or laboratory with very little sleep. At night I

would get sleepy, and go to the washroom to recuperate. On one

occasion, one of the informers saw my head down below the door of the

stall, and reported me to the foreman. Fortunately for me, I left

just before he came storming in. I am sure they would have fired me

if they caught me sleeping on Government time!

Night Work — Day School

That year (1935) the Congressional session went

through the whole summer, so I took advantage of my night work to

take a course in organic chemistry in the daytime. The whole year’s

work was to be completed during two six-week marathons of five

classes and five labs a week. My grade for the first term was a "C",

largely, I believe, because I could not get acceptable yields in my

experiments, and because I forgot the structure of one dye on the

final exam. I didn't take the second term that summer, as it

overlapped National Guard camp. I planned to take it the following

spring, when Congress would again be in session, and I could work at

night.

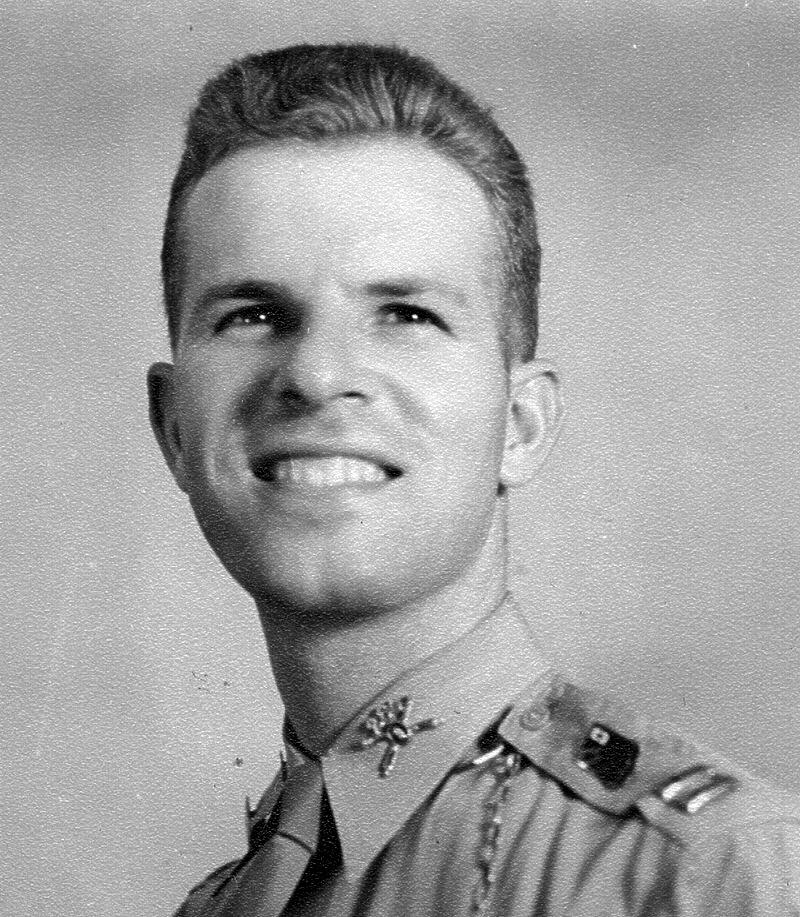

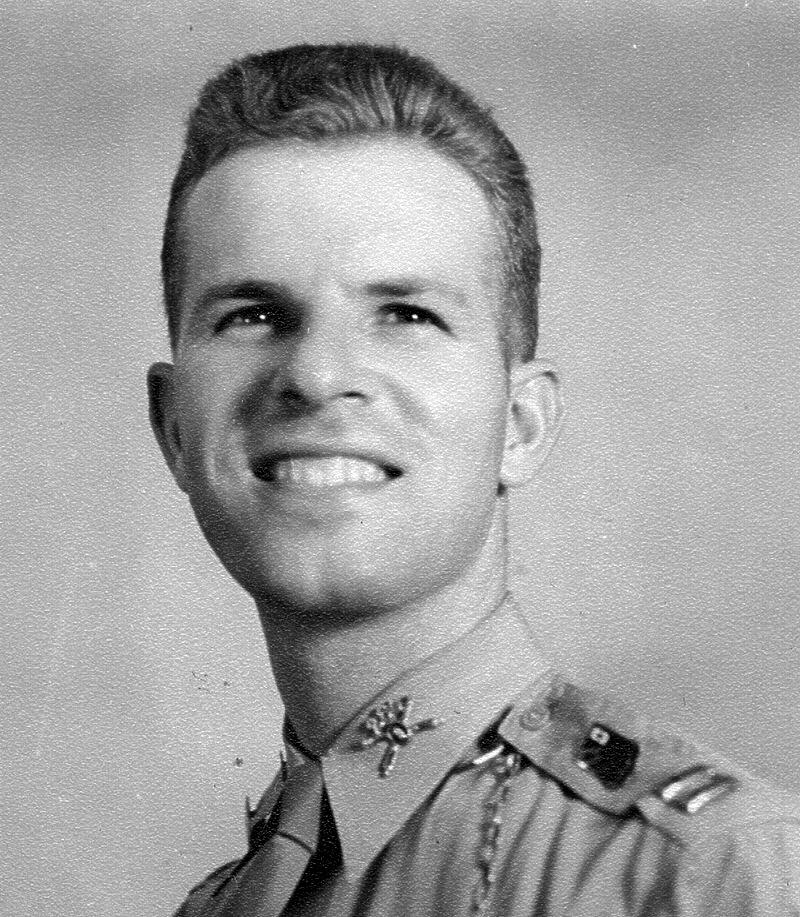

An Officer and a Gentleman

With the success

of Hitler in rearming Germany, attention was being called to our

pitiful Army, and the National Guard was one of the first areas of

"defense" to be beefed up. Our regiment was considerably

enlarged, and more officers were needed. I took the competitive

examination along with a dozen or so other sergeants but was not

ranked high enough to be commissioned before camp. Our regimental

commander, Colonel Burns, gave me the position of master sergeant

(the only one in the regiment), however, and I went to camp as the

highest ranking non-commissioned officer the Army had at that time.

As I was only 21, and looked it, the regulars at Fort Monroe once

told me as I was rushing to a formation, "Take it easy, buddy;

you’ve got everything!" The first sergeant, who had

previously had no competition as senior NCO in the battery, now had

to recognize that I technically outranked him. The captain came up

with the compromise that the first sergeant would be in charge of the

battery at infantry drill, and I would be in charge at artillery

drill. The man who actually maintained our equipment as a full-time

civilian employee at the armory couldn’t score well on a

written examination, and was not at all pleased to see me get the

job. However, after camp was over and more officer vacancies were

allotted to our regiment, I was commissioned a second lieutenant and

he was made master sergeant. The fact that I had already been a

second lieutenant in the high school cadet corps, with the same Sam

Browne belt and saber, took some of the prestige out of the event for

me, but my rapid promotion (due solely to the expansion of our

regiment) soon made up for it.

The worst part of the year was

when Mary Charlotte got involved with some girls at school who were

caught smoking, and all were campused for six weeks. I considered

that as most unfair to a young man who was head over heels in love,

particularly as she had not actually smoked. But Mrs. Bushnell was

the law at Mary Washington College, as I had been reminded many times

by Mary Charlotte, when matters of proper and improper conduct were

discussed between us.

Deep Dark Secret

On August 24, 1935, Mary

Charlotte’s best friend, Teenie Smith, and her boyfriend Norman

Kerlin, went to Ellicott City (near Baltimore) to get married

secretly. We went along with them, and decided almost at the last

minute to do the same thing. Mary Charlotte had already planned (and

I believe announced) that our wedding would be in June 1936, but that

seemed very far away after nearly a year of betrothal. Although it

was all supposed to be hush-hush, Teenie and her husband revealed

their relationship, but Mary Charlotte and I stoutly denied having

done likewise. To this day we have said nothing to anyone about it!

We were duly punished for our "sin" by — of all

things — a filibuster in the US Senate! Louisiana’s

Senator Huey Long chose August 24, 1935, to make one of his famous

filibusters. At least four times during that interminable night I

went to the foreman and asked to be excused, but I could not tell him

why, and he said "No!" When I finally got released, it was

five-thirty in the morning — hardly a time to get to know your

new wife! When Mary Charlotte came to Washington with me on week-ends

during the following school year, we registered in the Dodge Hotel as

Mr. and Mrs. Rodney Fitzgerald. We managed to keep the secret, not

only during the year until we were publicly married in June 1936 in

the church in Newport News, but all the years since.

That Christmas season Dad took Mother to Florida, and the house was

vacant. I took the occasion to have Mary Charlotte with me at the

house on one of those week-ends. Dad had turned off the water before

he went, but I turned it back on, and then neglected to drain the

pipes (as he had done) when turning it back off. When Mother and Dad

returned, they found that the water had frozen in the pipes of the

hot-water heating system, ruining them, and requiring the whole

system to be replaced. That was a blessing in disguise, as the old

coal furnace had nearly killed the whole family several years before,

because of carbon-monoxide gas generation. But Dad soon learned who

had turned on the water, and required me to pay half the cost of the

new system. He didn’t inquire very closely as to the

circumstances of our being there.

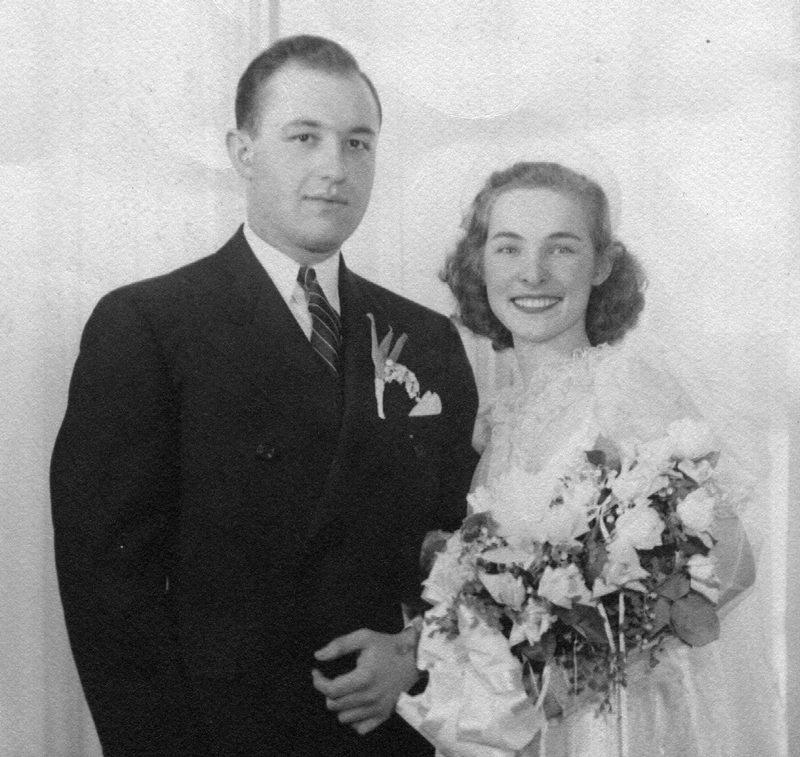

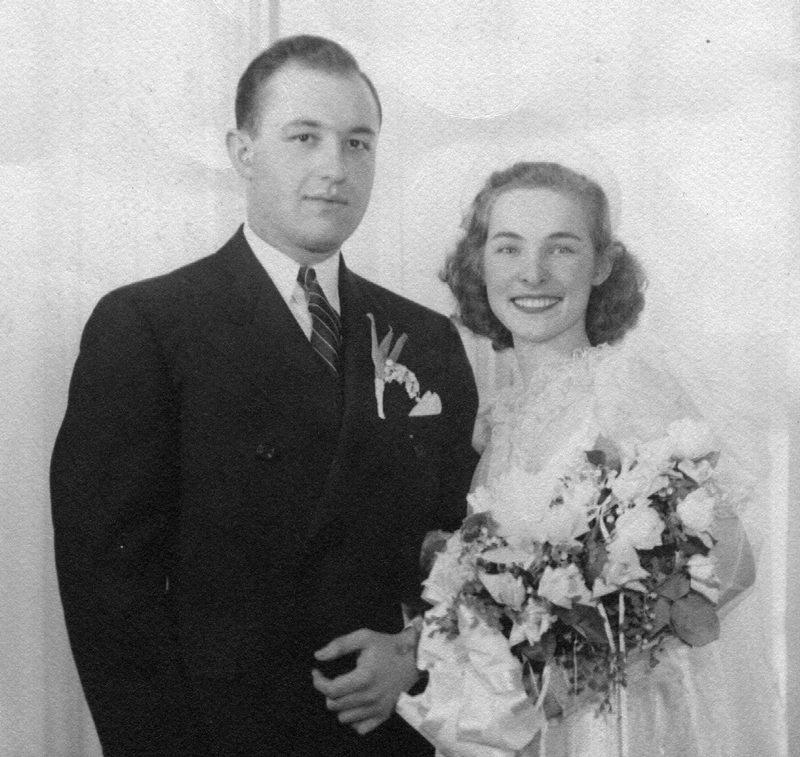

Wedding Bells

All during the spring of 1936, Mary Charlotte worked on her wedding

plans. The date was to be June 20th (a Saturday), and it was to be a

noon wedding with the groom and groomsmen in formal attire (see

left). I had selected Charlie Haig to be best man, and Mary had

chosen Teenie Kerlin as her matron of honor, since they were the ones

who had brought us together for the first time. My groomsmen were

fellow former apprentices who were also fellow National Guardsmen.

Mary’s bridesmaids (see right) were her classmates in

college but also included my sister Mary Jo as bridesmaid and my niece Margery Huff

as flower girl.

All during the spring of 1936, Mary Charlotte worked on her wedding

plans. The date was to be June 20th (a Saturday), and it was to be a

noon wedding with the groom and groomsmen in formal attire (see

left). I had selected Charlie Haig to be best man, and Mary had

chosen Teenie Kerlin as her matron of honor, since they were the ones

who had brought us together for the first time. My groomsmen were

fellow former apprentices who were also fellow National Guardsmen.

Mary’s bridesmaids (see right) were her classmates in

college but also included my sister Mary Jo as bridesmaid and my niece Margery Huff

as flower girl.

Her

church was the place, and her family had gone all out to decorate it

for the big event. In the picture on the left (back row) are

Mary Charlotte's mother's brother Claude Montgomery and the bride and

groom; (front row) Mary Charlotte's parents (Sudie and George

Chapman) and my mother and father. The wedding was set for twelve

o’clock, but didn’t actually get started until well after

twelve because Charlie Haig, who brought one of the bridesmaids from

her home, was late in bringing her to have her dress fitted.

Her

church was the place, and her family had gone all out to decorate it

for the big event. In the picture on the left (back row) are

Mary Charlotte's mother's brother Claude Montgomery and the bride and

groom; (front row) Mary Charlotte's parents (Sudie and George

Chapman) and my mother and father. The wedding was set for twelve

o’clock, but didn’t actually get started until well after

twelve because Charlie Haig, who brought one of the bridesmaids from

her home, was late in bringing her to have her dress fitted.

Since

National Guard camp was only a few weeks away, and I had planned a

six-week wedding trip to the West Coast, Mexico and Canada, we had a

mini-honeymoon in New York City. I can remember driving through

Baltimore on our way to New York, when I became involved in an

altercation with a local driver. I had passed him, and cut back into

line too close to his car for his liking, so he passed me and

deliberately banged my left front fender. I immediately stopped and

got out, as he did. He then walked up to me and hit me in the left

eye with his fist. Not wishing to end up in jail on my wedding night,

I refrained from hitting back (or maybe I was too cowardly!). We

resumed our journey, and as luck would have it I saw a motorcycle cop

just up the road. Coming abreast of him, I told him to stop the

driver in the car ahead, which he did. After taking us to a side

street, he got the story and saw my black eye. He advised me to take

$2 to repair my fender and not charge the man, as I would then have

to appear in court the following Monday. I suppose I looked rather

suspicious with that black eye when Mary Charlotte and I checked into

our New York hotel at five-thirty the next morning.

The only

event of that week in New York that I remember was the night at Billy

Minsky’s burlesque theater on Times Square, which featured

strip-tease artists. Bob and Margaret (who lived in nearby New

Jersey) had invited us to go as their wedding present. Neither of us

had ever been to such a place, but we had heard all about them. I’ll

never forget my embarrassment at Mary Charlotte’s shriek when

the first girl bared herself to the waist.

Shortly after the

wedding, Dad had an announcement placed in the local county paper,

which published it under the headline "Mr. Mitchell marries

belle of Virginia." For years afterward, Dad would address Mary

Charlotte as "Bridey Belle."

Our National Guard

regiment went to Virginia Beach that year, much to my disappointment,

as it was too far to be with Mary Charlotte at her Newport News home.

As a rookie shave-tail, I got the low end of the stick in

assignments, but did have the job of preparing the formal reports of

the target practice. I’ll never forget the dig I got from

Captain Bullis of E Battery (which I later commanded as captain) for

not knowing that the score had to be multiplied by four, for the four

AA machine guns involved. He made me recalculate the whole thing,

although that was the only error.

Our Wedding Trip

Our

wedding trip was something else! (see left, but taken much later)

I had acquired another second-hand car, the engine of which John King

had overhauled, working almost all the night before we left to get it

finished. In those days, one had to drive 500 miles at 25 miles an

hour to break in new piston rings, and there was no time to do this

before leaving. So we drove nearly all the way to central Tennessee

at 25 miles an hour, stopping at Bristol for a few hours rest, but

not reaching Mary Charlotte’s relatives’ home in

Lewisburg until mid-afternoon. Nearly all her many Tennessee

relatives had gathered for a welcoming lunch, but by the time we

arrived many of them had left. In Kansas we spent the night with one

of Mother’s friends that I didn’t remember ever having

seen before. We had only enough time with them to eat meals and sleep

— hardly a good way to get acquainted with one’s friends.

We found out how hot it can be in August in Kansas, but who could

then afford rooms with air conditioning (which was available only in

the most expensive hotels). We went to Estes Park in the Rockies, and

I tried to realize a lifetime ambition by climbing to the top of one

of the major peaks — Long’s Peak. We got a late start,

and rented horses which brought us to the timber line. Mary Charlotte

had had enough by then, and waited for me to climb alone to the

continental divide, where I could look out over the Great Plains to

the east, but time didn’t permit going any higher, and I never

got another chance!

Our

wedding trip was something else! (see left, but taken much later)

I had acquired another second-hand car, the engine of which John King

had overhauled, working almost all the night before we left to get it

finished. In those days, one had to drive 500 miles at 25 miles an

hour to break in new piston rings, and there was no time to do this

before leaving. So we drove nearly all the way to central Tennessee

at 25 miles an hour, stopping at Bristol for a few hours rest, but

not reaching Mary Charlotte’s relatives’ home in

Lewisburg until mid-afternoon. Nearly all her many Tennessee

relatives had gathered for a welcoming lunch, but by the time we

arrived many of them had left. In Kansas we spent the night with one

of Mother’s friends that I didn’t remember ever having

seen before. We had only enough time with them to eat meals and sleep

— hardly a good way to get acquainted with one’s friends.

We found out how hot it can be in August in Kansas, but who could

then afford rooms with air conditioning (which was available only in

the most expensive hotels). We went to Estes Park in the Rockies, and

I tried to realize a lifetime ambition by climbing to the top of one

of the major peaks — Long’s Peak. We got a late start,

and rented horses which brought us to the timber line. Mary Charlotte

had had enough by then, and waited for me to climb alone to the

continental divide, where I could look out over the Great Plains to

the east, but time didn’t permit going any higher, and I never

got another chance!

We went from national park to national

park — Yellowstone, Mesa Verde, Cedar Breaks, Zion, and then on

to Seattle and Vancouver. When we had finished our lunch (for 25

cents apiece) at a delightful little restaurant in Vancouver, I

discovered to my horror that I had lost my wallet. Fortunately, Mary

Charlotte had some money and we could pay for the meal and call the

motel in Bellingham where we had spent the night. Much to our relief

the motel owner had found the wallet (with my two-weeks pay I had

just picked up at the Seattle post office) under my pillow where I

had placed it the night before for safe keeping. We got it on our

return to Seattle. In Yosemite, I got a picture with our 8-mm color

camera of a bear cub, which Mary Charlotte had tried to pet. We went

to Los Angeles, San Diego and Tia Juana, and then back east through

Arizona and New Mexico to El Paso, thence along the Rio Grande to

Laredo. I remember one stretch of highway where we drove for more

than an hour without seeing another person, car, or animal!

At

Laredo, the room at the motel was so filthy that Mary Charlotte

wouldn’t sleep on the bed provided, so we set up our camping

cots in the motel room. The Trans-Americas Highway to Mexico City was

still under construction, and we had 70 miles of torn-up road to

negotiate. Near the end of it our second tire blew, and we had to

leave the car on the highway and take a "bus" to Jacala,

the next town. The bus was an old truck with wooden planks on

sawhorses for seats, and the driver drove through mountain fog at

full speed when I could not even see the road beneath us. But we got

to the town and spent the night there while waiting for our tires to

be repaired. The "motel" had only one john for the entire

place — a full-sized room with only the toilet in it, and no

door — common gender! A returning tourist graciously gave us a

ride back to our car, which was undisturbed during our 24-hour

absence. Returning from Mexico, I ran out of money, so drove

continuously for over 1,000 miles from Mexico City to Austin, Texas.

In Dallas, a State fair was being held and a friend of Marion’s

(from her Senator’s office) was in charge of exhibits. We

eventually contacted him and he gave us a draft on Mother for $40,

the amount we had written to her to send to us "either at Dallas

or New Orleans." Of course, she had sent it to New Orleans, but

we went broke in Dallas, after registering, at Mary Charlotte’s

insistence, at the Adolphus Hotel, one of Dallas’ finest.

Mother had a hard time with that draft, as it took over six weeks for

her to get her money back from New Orleans. I remember going to the

dining room for dinner, and being told I had to have a necktie. I was

too tired to eat, but Mary Charlotte insisted, so the waiter got me a

tie and I watched her eat, although I couldn’t. At Memphis, we

stopped at Sears Roebuck to get our tire guarantees honored, and got

three new tires at $1.50 apiece. We went broke again in Tennessee and

borrowed $10 from Mary Charlotte’s uncle, Claude Montgomery.

This got us to Bristol VA with 21 cents after paying our motel bill,

and filling the gas tank — 425 miles from home. We decided to

go to Newport News (which was closer) and went all day at modest

speed, coasting down every hill to save gas. We managed to get to

Norfolk, where the 21 cents bought a gallon of gas and paid for a

telephone call to the home of one of Mary Charlotte’s

classmates in Portsmouth. I can still remember how good those

sandwiches tasted at 3pm after nothing to eat since the night before.

The next few months were tight financially as we had to settle up all

our borrowings, but we eventually cleared the deck after our

13,607-mile odyssey.

Mary Charlotte went back to school for

her senior year that autumn, having already earned her "MRS",

but she also wanted her "BS". I got a jolt when told by the

school that I would have to pay out-of-state tuition rates for her,

as they considered her residence to be where her husband lived. It

was nice to be above-board with our living together, even if it was

only week-ends.

My time at George Washington University in

1936 was spent on furthering my training in engineering, in

completing Organic Chemistry, and getting started on modern physics.

It was a good thing for both of us that Mary Charlotte was at

Fredericksburg during the week, as work, school, and National Guard

completely occupied my waking hours (which were all too many). I

learned later what charity some of my GW profs exhibited, when the

class would be diverted from the lecture by my bobbing head, some

even betting on whether or not I would break my neck! At work one

night, the desk clerk (who didn’t like ex-apprentices) gave me

the last piece of copy for the Congressional Record, and made it

three times as long as it should have been. I could hardly keep my

eyes open as I set it up, and fell asleep at the machine a dozen

times or so, judging from the proof that came back to me, so badly

marked up that the original type could hardly be seen. It showed the

bull headedness of these people that they made me reset the copy, and

the foreman had to stay overtime to get the final okay proofs to the

press room for printing the Congressional Record. Needless to say, I

did not get on the night side the following year!

Sailing the Matrimonial Seas

College

graduation had brought with it the need to find a place to live. One

of Mary Charlotte’s classmates had acquired a new home in the

fashionable part of Washington’s suburbs that was a financial

burden to her and her doctor husband, and persuaded us to take a room

with them for a few months, which we did. Never again would we want

to live in someone else’s home! So in early January we moved to

an apartment at 3432 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, where we would

live for the next 3-1/2 years. It was a good choice for us, both

geographically and financially, and we enjoyed those months, busy as

they were. We had not had a church home since Mary Charlotte had

given up her childhood relationship with the Presbyterian Church in

Newport News. I don’t remember why, but we started going to the

Gunton-Temple Presbyterian Church on 16th Street (NW) shortly after

locating at 3432 Connecticut Avenue. We liked it, and I even taught

Sunday School. When it came time for Mary Jo and Clyde Balch to be

married (April 1940), Mary Jo selected that church for the wedding,

even though she had Rev. Custis perform the ceremony. Mary Charlotte

tried several different vocations — waitress (one day!),

typist, file clerk, and teaching (she held a teaching certificate in

Virginia). Several months at Strayers Business College convinced her

that she was not cut out for the business world, so she contented

herself with occasional substitute teaching at nearby Washington

elementary schools.

College

graduation had brought with it the need to find a place to live. One

of Mary Charlotte’s classmates had acquired a new home in the

fashionable part of Washington’s suburbs that was a financial

burden to her and her doctor husband, and persuaded us to take a room

with them for a few months, which we did. Never again would we want

to live in someone else’s home! So in early January we moved to

an apartment at 3432 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, where we would

live for the next 3-1/2 years. It was a good choice for us, both

geographically and financially, and we enjoyed those months, busy as

they were. We had not had a church home since Mary Charlotte had

given up her childhood relationship with the Presbyterian Church in

Newport News. I don’t remember why, but we started going to the

Gunton-Temple Presbyterian Church on 16th Street (NW) shortly after

locating at 3432 Connecticut Avenue. We liked it, and I even taught

Sunday School. When it came time for Mary Jo and Clyde Balch to be

married (April 1940), Mary Jo selected that church for the wedding,

even though she had Rev. Custis perform the ceremony. Mary Charlotte

tried several different vocations — waitress (one day!),

typist, file clerk, and teaching (she held a teaching certificate in

Virginia). Several months at Strayers Business College convinced her

that she was not cut out for the business world, so she contented

herself with occasional substitute teaching at nearby Washington

elementary schools.

Mary Charlotte’s father had failed

in health very noticeably during the first half of the year, and he

finally died in July, when I was in National Guard camp at Virginia

Beach. The family tried unsuccessfully to reach me, so I was unable

to attend the funeral. Mrs. Chapman now was faced with living alone,

which she did until 1948, when she came to live with us for the rest

of her life.

My request to be transferred to the night side

for the congressional session of 1937 was denied, even though I got a

nice letter from Senator Connally. I’m sure the turn-down was

due to the incident of my sleepiness on that last piece of copy for

the Congressional Record, described earlier. Even so, I was able to

take several engineering lab courses without infringing upon my

National Guard nights (Tuesdays and Thursdays).

The big event

of the year, for me, was the opportunity to attend the 3-month

special course for National Guard and Reserve officers at the Coast

Artillery School, Fort Monroe. Not only would this be a valuable

asset in my National Guard career, but I got my full pay from the GPO

as well as my pay as a first lieutenant. All my absences from the GPO

for military duty were considered as paid (military) leave, much to

the disgust of the powers that be at the GPO. Another officer from my

regiment, Robert Martin (6-foot-4, 250-pound ex-Texan who worked for

the US Weather Bureau) and I boarded with Mary Charlotte’s

mother while attending the school. Jo-Bob, as we called him (his full

name was Robert Joseph Michael Cameron Kent Martin) could eat six

meals a day! Mrs. Chapman thought she had not put enough food on the

table if there was less food left than had been consumed, but Jo-Bob

delighted in "finishing things up." He was such a lot of

fun — never sour, never critical. It was a very good three

months! I remember one senior instructor, Major Townsend, was quite

taken aback at my brashness on one occasion. He had just written a

very involved formula on the blackboard which represented the

calculation necessary to determine the trajectory of a shell after it

had been fired from a gun. I raised my hand and asked if one of the

signs in the formula shouldn’t have been "+" instead of

"-" as he had written it. When he checked his notes, he

found I was right. I never did tell him that the square root of a

negative number could not be calculated in the ordinary number domain

— one of the things I had just learned in my math courses. He

was later instrumental in getting me my most rewarding war-time

assignment.

College Graduate

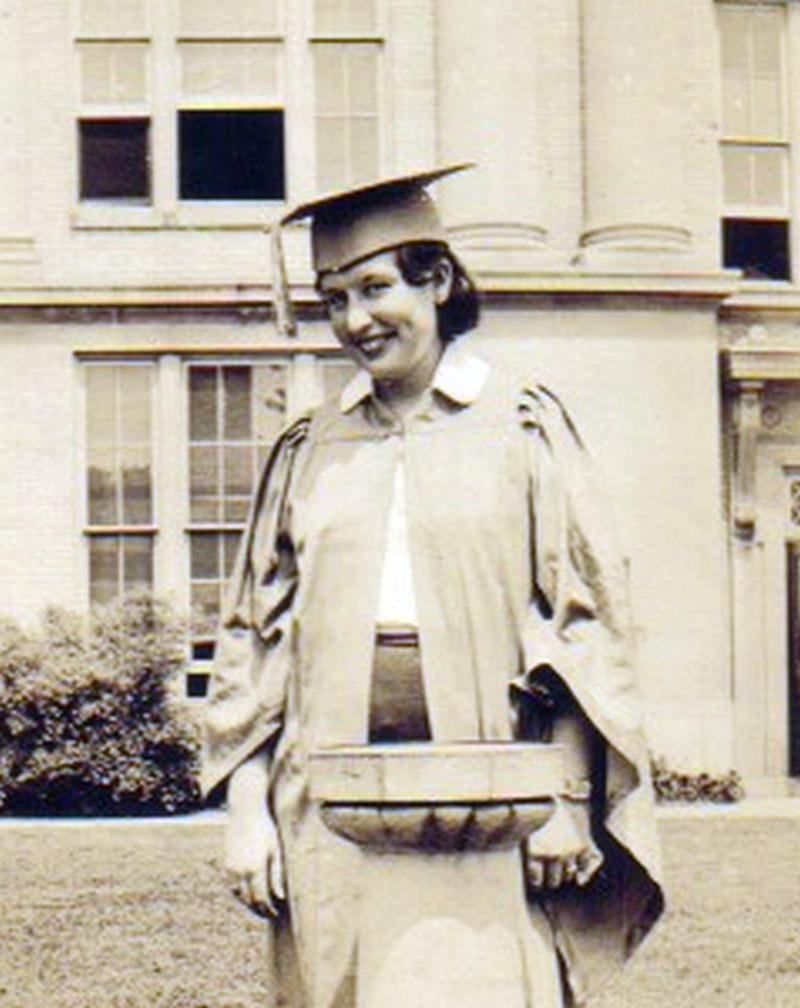

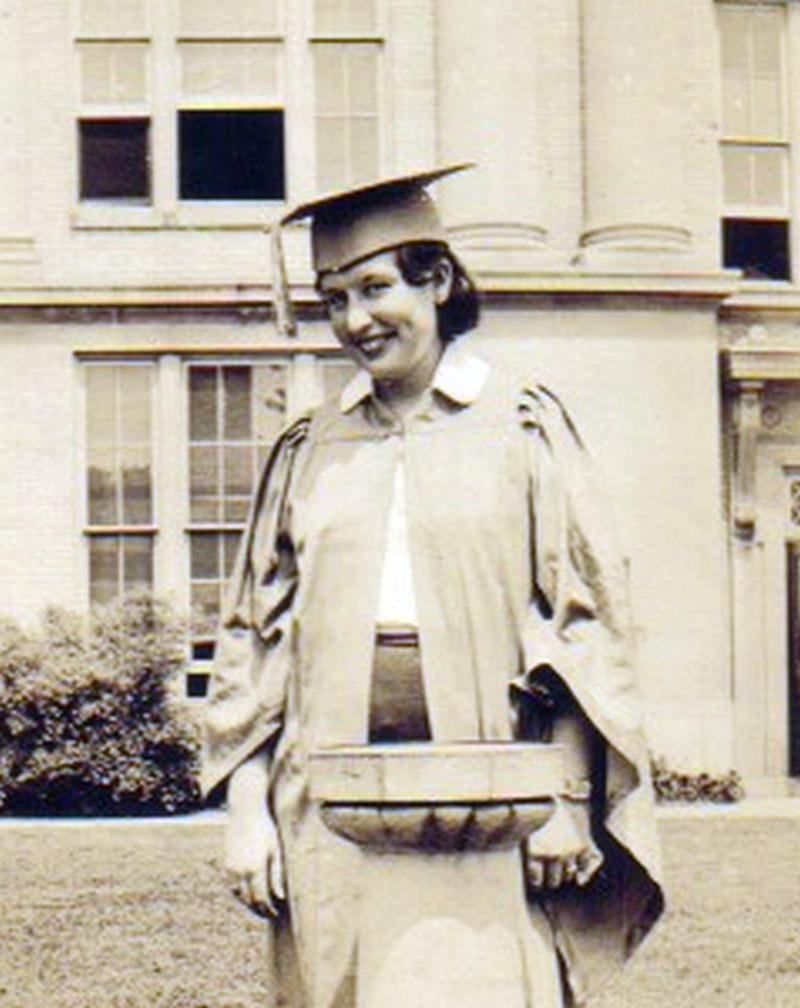

Both

my younger sister and my younger wife (see left) had graduated

from college, and it was now my turn. My attendance at the Coast

Artillery School the preceding autumn had prevented me from taking an

essential EE lab course, but the EE prof, Norman Bruce Ames,

graciously allowed me to attend the first semester of that course

with another group while taking the second semester. I also had to

complete a course in public speaking — required only for EE

students, as Prof. Ames stoutly maintained that an engineer should be

able to speak publicly. Although I thought it a complete waste of my

valuable time, I had no choice but to take the course. As I look back

on it, that course had greater benefit for me in later life than any

other college course I ever took! Although my cadet and National

Guard training had taught me to speak to groups of people, making

formal public speeches was something I had done only once in my life

— at church many years before. Each of us in the class had to

make three speeches during the semester, one of which was to be

humorous. One of the students spoke on the three queens of burlesque,

and "brought the house down." Thus I was emboldened to

speak on "The Engineer Selects a Wife," which went over

quite well. I have often wondered since if some of the best years of

my life would have been so good had I not had that preparation in

public speaking.

Both

my younger sister and my younger wife (see left) had graduated

from college, and it was now my turn. My attendance at the Coast

Artillery School the preceding autumn had prevented me from taking an

essential EE lab course, but the EE prof, Norman Bruce Ames,

graciously allowed me to attend the first semester of that course

with another group while taking the second semester. I also had to

complete a course in public speaking — required only for EE

students, as Prof. Ames stoutly maintained that an engineer should be

able to speak publicly. Although I thought it a complete waste of my

valuable time, I had no choice but to take the course. As I look back

on it, that course had greater benefit for me in later life than any

other college course I ever took! Although my cadet and National

Guard training had taught me to speak to groups of people, making

formal public speeches was something I had done only once in my life

— at church many years before. Each of us in the class had to

make three speeches during the semester, one of which was to be

humorous. One of the students spoke on the three queens of burlesque,

and "brought the house down." Thus I was emboldened to

speak on "The Engineer Selects a Wife," which went over

quite well. I have often wondered since if some of the best years of

my life would have been so good had I not had that preparation in

public speaking.

The graduation itself has left me no memories

whatever. As far as I was concerned it was only a means to an end. I

wanted to get a doctorate, and the bachelor’s degree was the

first step. I cannot explain why I chose the field of physics for my

next degree. While I was fascinated with atomic physics, the

practical things of heat, light, and sound left me cold. I liked the

mathematical side but not the experimental side. My professor of a

course in quantum physics was a one-legged recent immigrant named

Edward Teller, later to be called the father of the H-bomb. My other

physics prof was Dr. Benjamin Brown, as different from Teller as day

is from night. But along with Prof. Ames, these two men gave me an

understanding of their fields which sustained me in many ways in my

own career. I might just as well not have taken the other

courses!

When I got back to the GPO from the three-month

course at the Coast Artillery School, I found that I had been

transferred to the Patents Department. If there is anything more dull

than setting patent specifications, then I certainly don’t want

to experience it. I could work for a solid hour and then not be able

to tell you even the general nature of the spec I had been composing.

For three years, this was to be my daily work, however, and it did

rub off on me. I got to the point of describing the workings of

electrical machinery and electronic devices in patent terminology,

which I am now sure must have turned my listeners off. I did have the

temerity of taking the civil service examination for patent examiner,

but I found my exposure to patent lingo harmed rather than helped me

in that effort, and I didn’t qualify.

Things in Europe

had been getting blacker and blacker, with Hitler’s and later

Mussolini’s successes in establishing their military machines.

Congress had at long last begun to beef up our Armed Services, and

the antiaircraft was in the forefront of that build-up. Our regiment,

which had only four batteries when I enlisted, had grown to six or

seven, and promotions were coming much more rapidly than usual in

peace time. I had been a second lieutenant for less than a year when

I got my silver bar as a first. My service as such was split between

an AA gun battery and regimental staff. I remember one drill night

when we had a military visitor to the HQ. When I went to introduce

him to the regimental executive officer, Lt. Col. Mann, I couldn’t

think of Col. Mann’s name! For the remainder of my time in the

260th, I believe that officer held that against me. Nevertheless,

since promotion was strictly by seniority, my time was soon coming

when I could put on the coveted twin bars of a captain.

War in Europe

Those

bars became a reality early in 1939, and I was given command of

Battery E, formerly "belonging" to now-Major Bullis. This

was my first experience with automatic weapons, and it was a little

awkward to learn from the top! Even before the promotion came, I had

another training course opportunity, this time at Fort Meade, just a

few miles away in Maryland. Here I was introduced to map warfare, as

we students re-fought on maps some of the Civil War battles. At the

conclusion of the course I was given a certificate of capacity as

major, and I hadn’t even made captain yet! My only recollection

of these two weeks was a lunch at the officer’s club. I was

staying at Mother’s house in nearby Hyattsville, but even so

had to leave at six-thirty in the morning to get to class by eight.

So by lunch-time I was starving. This day the no-options menu was

liver and turnips, the one meat and one vegetable I thoroughly

detested — but I ate them.

Those

bars became a reality early in 1939, and I was given command of

Battery E, formerly "belonging" to now-Major Bullis. This

was my first experience with automatic weapons, and it was a little

awkward to learn from the top! Even before the promotion came, I had

another training course opportunity, this time at Fort Meade, just a

few miles away in Maryland. Here I was introduced to map warfare, as

we students re-fought on maps some of the Civil War battles. At the

conclusion of the course I was given a certificate of capacity as

major, and I hadn’t even made captain yet! My only recollection

of these two weeks was a lunch at the officer’s club. I was

staying at Mother’s house in nearby Hyattsville, but even so

had to leave at six-thirty in the morning to get to class by eight.

So by lunch-time I was starving. This day the no-options menu was

liver and turnips, the one meat and one vegetable I thoroughly

detested — but I ate them.

The captain of a National

Guard battery had to do his own recruiting, and if he did not have at

least 60% attendance on a drill night, the officers did not get paid.

We had a new Regular Army instructor named Col. Villaret. He was a

stickler for smart appearance and our old moth eaten discarded Army

overcoats dismayed him. On my second or third drill night as captain

he threatened not to allow about a third of my men to be counted

because they had buttons missing on their overcoats! I don’t

know who straightened him out, but he quickly abandoned that approach

and became a valuable tutor to us in the important things of

soldiering. The rapid expansion of our regiment had put a strain on

our recruiting abilities, and I was almost desperate to find new men.

I talked to all my colleagues at the GPO, including Ken Romjue, one

of those who had made consistent 100’s on his weekly spelling

tests during our apprenticeship. Ken succumbed to my solicitations,

and became a private in Battery E. He later made sergeant, and by

taking correspondence courses, qualified as reserve second

lieutenant. This allowed him later to be called to active duty as a

first lieutenant, and he finished the war as a lieutenant colonel.

His closest buddy at the GPO, William "Dusty" Rhodes,

however, would have none of us. He was later drafted and spent the

entire war as an enlisted man in the South Pacific.

Our

regiment was supposed to take tactical training every third year,

that is, go on an extended maneuver for the two weeks, and we had

done so in 1931 and in 1934. So, after five years, we were ordered to

do so in 1939, having been equipped with modern trucks and weapons.

Col. Burns chose the nearby Virginia area in the vicinity of

Appomattox Courthouse, which we dutifully provided with antiaircraft

protection. My battery ('E') was assigned to protect the regimental

headquarters, which put me under the thumb of Lt. Col. Mann, our

regimental executive. Since the headquarters battery had just been

formed, it was low in manpower and experience, and Col. Mann kept

calling on my battery for details of men for this or that menial

task. I refused to strip my gun crews, and sent men from my own

battery HQ. Finally, only the first sergeant and I were left, and we

received a demand for two men to build a privy for the officers. So

he and I took our hammer and saw and trudged off to Regimental

Headquarters, working most of the morning on a three-holer. Not

having a keyhole saw, we made the holes square, and this brought the

gibe from everyone that we were expecting round butts to fit in

square holes. This incident did lessen the demands for details, but

it didn’t improve my standing with Col. Mann any!

In

September Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and World War II began. Our

regiment was given extra active duty during the month of December,

two days each of the four week-ends. There was frenzied scrambling to

beef up our defenses, and soon I was notified of inspection after

inspection of every kind of equipment we were supposed to have. As

each one meant a day of military leave from the Patents Department,

my boss there — a real tyrant named Broderick — breathed

fire and brimstone each time I went to him with an order for my

presence at the inspection. But he was helpless in this particular

matter, and had to let me off.

The advent of the European War

made my National Guard work top priority for me, but I continued with

my graduate physics studies at GW. One of my courses was a seminar in

theoretical physics, under another recent import from Europe, Dr.

George Gamow. He was a tall, Viking-like person, whom I seldom saw,

as my assignments were mostly in physics journals. One major topic I

had to pursue was cosmic rays. I found that a fascinating subject, as

these extremely high-energy particles that come from outer space into

our earthly environment are supposed to cause, among other things,

the mutations in DNA said to be responsible for evolution.

1940 — The Year of Anticipation

The

major family event of 1940 was Mary Jo’s marriage to Clyde

Balch (see left) on April 14, 1940. It was held in our church

of the time, Gunton-Temple Presbyterian, on 16th Street (as earlier

mentioned). I don’t have a wedding picture, but this is a good

one of the couple. The wedding must have drawn a family gathering, as

the picture to the right shows (left to right) Marion with Bobby

Caruthers in front of her, Uncle Wilbur holding Lynne Caruthers, Mary

Charlotte, Margaret, Mother and Dad (with Bob Caruthers in the

background).

The

major family event of 1940 was Mary Jo’s marriage to Clyde

Balch (see left) on April 14, 1940. It was held in our church

of the time, Gunton-Temple Presbyterian, on 16th Street (as earlier

mentioned). I don’t have a wedding picture, but this is a good

one of the couple. The wedding must have drawn a family gathering, as

the picture to the right shows (left to right) Marion with Bobby

Caruthers in front of her, Uncle Wilbur holding Lynne Caruthers, Mary

Charlotte, Margaret, Mother and Dad (with Bob Caruthers in the

background).

Back to the military, our regiment had been

brought up to its full number of units this year, and given Table-of-

Organization equipment. For our summer training we were ordered to

take part in the First Army maneuvers in northern New York State.

This was new territory for most of us, and we certainly didn’t

anticipate the frost on our pup tents during the August nights.

Although we had adequate woolen blankets, our summer khakis were no

protection from the cold morning winds. Only the bravest dared to

swim in the ice-cold rivers nearby, and recreation was hard to come

by. One of the local people quipped that Ogdensburg has only two

seasons — July and winter.

Our regimental commander,

Col. Walter Burns, evidently had some contacts with the First Army

brass, because he told us that we were going to be called into

Federal service soon, and his prediction was that it would last at

least five years. His prediction was uncannily accurate. We were in

Federal service six months later, and my period of service was five

years, one month and ten days. Congress had hastily installed the

draft right after WWII had started the year before, but the debate

was bitter about continuing it at the end of its first year —

the continuation hung on one vote! At the same time Congress voted to

call up the nation’s National Guard units for a year’s

training, and we were on pins and needles awaiting our call.

When

we left on the summer maneuvers, we were so sure that we would not

return to civilian status that I gave up our Connecticut Avenue

apartment, sold our furniture, and parked Mary Charlotte in Mother’s

house while I was on duty. However, it soon became evident that our

Federal call was months — not days — away, so we rented a

furnished apartment month by month in the 1800 block of Columbia

Road.

I didn’t even bother to register at GW that

autumn, but I did wind up my course work for a master’s in

physics that spring. GW required a thesis for the degree in addition

to classwork, and my National Guard activities left me no time or

energy to compose one. The highlight of that work in graduate physics

was a report to the class by Dr. Brown of the work of Lisa Meintner

in Central Europe of the fissioning of a uranium atom. We eagerly

asked if this presaged the development of atomic energy, but Dr.

Brown was skeptical, as it seemed to take more energy to fission the

atom than was produced. It was some three years later that another

experiment in Chicago proved otherwise, and the first successful

release of atomic energy took place, leading almost immediately to

the A-bomb.

Go to next

chapter

Return to Table of Contents

All during the spring of 1936, Mary Charlotte worked on her wedding

plans. The date was to be June 20th (a Saturday), and it was to be a

noon wedding with the groom and groomsmen in formal attire (see

left). I had selected Charlie Haig to be best man, and Mary had

chosen Teenie Kerlin as her matron of honor, since they were the ones

who had brought us together for the first time. My groomsmen were

fellow former apprentices who were also fellow National Guardsmen.

Mary’s bridesmaids (see right) were her classmates in

college but also included my sister Mary Jo as bridesmaid and my niece Margery Huff

as flower girl.

All during the spring of 1936, Mary Charlotte worked on her wedding

plans. The date was to be June 20th (a Saturday), and it was to be a

noon wedding with the groom and groomsmen in formal attire (see

left). I had selected Charlie Haig to be best man, and Mary had

chosen Teenie Kerlin as her matron of honor, since they were the ones

who had brought us together for the first time. My groomsmen were

fellow former apprentices who were also fellow National Guardsmen.

Mary’s bridesmaids (see right) were her classmates in

college but also included my sister Mary Jo as bridesmaid and my niece Margery Huff

as flower girl. Her

church was the place, and her family had gone all out to decorate it

for the big event. In the picture on the left (back row) are

Mary Charlotte's mother's brother Claude Montgomery and the bride and

groom; (front row) Mary Charlotte's parents (Sudie and George

Chapman) and my mother and father. The wedding was set for twelve

o’clock, but didn’t actually get started until well after

twelve because Charlie Haig, who brought one of the bridesmaids from

her home, was late in bringing her to have her dress fitted.

Her

church was the place, and her family had gone all out to decorate it

for the big event. In the picture on the left (back row) are

Mary Charlotte's mother's brother Claude Montgomery and the bride and

groom; (front row) Mary Charlotte's parents (Sudie and George

Chapman) and my mother and father. The wedding was set for twelve

o’clock, but didn’t actually get started until well after

twelve because Charlie Haig, who brought one of the bridesmaids from

her home, was late in bringing her to have her dress fitted. Our

wedding trip was something else! (see left, but taken much later)

I had acquired another second-hand car, the engine of which John King

had overhauled, working almost all the night before we left to get it

finished. In those days, one had to drive 500 miles at 25 miles an

hour to break in new piston rings, and there was no time to do this

before leaving. So we drove nearly all the way to central Tennessee

at 25 miles an hour, stopping at Bristol for a few hours rest, but

not reaching Mary Charlotte’s relatives’ home in

Lewisburg until mid-afternoon. Nearly all her many Tennessee

relatives had gathered for a welcoming lunch, but by the time we

arrived many of them had left. In Kansas we spent the night with one

of Mother’s friends that I didn’t remember ever having

seen before. We had only enough time with them to eat meals and sleep

— hardly a good way to get acquainted with one’s friends.

We found out how hot it can be in August in Kansas, but who could

then afford rooms with air conditioning (which was available only in

the most expensive hotels). We went to Estes Park in the Rockies, and

I tried to realize a lifetime ambition by climbing to the top of one

of the major peaks — Long’s Peak. We got a late start,

and rented horses which brought us to the timber line. Mary Charlotte

had had enough by then, and waited for me to climb alone to the

continental divide, where I could look out over the Great Plains to

the east, but time didn’t permit going any higher, and I never

got another chance!

Our

wedding trip was something else! (see left, but taken much later)

I had acquired another second-hand car, the engine of which John King

had overhauled, working almost all the night before we left to get it

finished. In those days, one had to drive 500 miles at 25 miles an

hour to break in new piston rings, and there was no time to do this

before leaving. So we drove nearly all the way to central Tennessee

at 25 miles an hour, stopping at Bristol for a few hours rest, but

not reaching Mary Charlotte’s relatives’ home in

Lewisburg until mid-afternoon. Nearly all her many Tennessee

relatives had gathered for a welcoming lunch, but by the time we

arrived many of them had left. In Kansas we spent the night with one

of Mother’s friends that I didn’t remember ever having

seen before. We had only enough time with them to eat meals and sleep

— hardly a good way to get acquainted with one’s friends.

We found out how hot it can be in August in Kansas, but who could

then afford rooms with air conditioning (which was available only in

the most expensive hotels). We went to Estes Park in the Rockies, and

I tried to realize a lifetime ambition by climbing to the top of one

of the major peaks — Long’s Peak. We got a late start,

and rented horses which brought us to the timber line. Mary Charlotte

had had enough by then, and waited for me to climb alone to the

continental divide, where I could look out over the Great Plains to

the east, but time didn’t permit going any higher, and I never

got another chance! College

graduation had brought with it the need to find a place to live. One

of Mary Charlotte’s classmates had acquired a new home in the

fashionable part of Washington’s suburbs that was a financial

burden to her and her doctor husband, and persuaded us to take a room

with them for a few months, which we did. Never again would we want

to live in someone else’s home! So in early January we moved to

an apartment at 3432 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, where we would

live for the next 3-1/2 years. It was a good choice for us, both

geographically and financially, and we enjoyed those months, busy as

they were. We had not had a church home since Mary Charlotte had

given up her childhood relationship with the Presbyterian Church in

Newport News. I don’t remember why, but we started going to the

Gunton-Temple Presbyterian Church on 16th Street (NW) shortly after

locating at 3432 Connecticut Avenue. We liked it, and I even taught

Sunday School. When it came time for Mary Jo and Clyde Balch to be

married (April 1940), Mary Jo selected that church for the wedding,

even though she had Rev. Custis perform the ceremony. Mary Charlotte

tried several different vocations — waitress (one day!),

typist, file clerk, and teaching (she held a teaching certificate in

Virginia). Several months at Strayers Business College convinced her

that she was not cut out for the business world, so she contented

herself with occasional substitute teaching at nearby Washington

elementary schools.

College

graduation had brought with it the need to find a place to live. One

of Mary Charlotte’s classmates had acquired a new home in the

fashionable part of Washington’s suburbs that was a financial

burden to her and her doctor husband, and persuaded us to take a room

with them for a few months, which we did. Never again would we want

to live in someone else’s home! So in early January we moved to

an apartment at 3432 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, where we would

live for the next 3-1/2 years. It was a good choice for us, both

geographically and financially, and we enjoyed those months, busy as

they were. We had not had a church home since Mary Charlotte had

given up her childhood relationship with the Presbyterian Church in

Newport News. I don’t remember why, but we started going to the

Gunton-Temple Presbyterian Church on 16th Street (NW) shortly after

locating at 3432 Connecticut Avenue. We liked it, and I even taught

Sunday School. When it came time for Mary Jo and Clyde Balch to be

married (April 1940), Mary Jo selected that church for the wedding,

even though she had Rev. Custis perform the ceremony. Mary Charlotte

tried several different vocations — waitress (one day!),

typist, file clerk, and teaching (she held a teaching certificate in

Virginia). Several months at Strayers Business College convinced her

that she was not cut out for the business world, so she contented

herself with occasional substitute teaching at nearby Washington

elementary schools. Both

my younger sister and my younger wife (see left) had graduated

from college, and it was now my turn. My attendance at the Coast

Artillery School the preceding autumn had prevented me from taking an

essential EE lab course, but the EE prof, Norman Bruce Ames,

graciously allowed me to attend the first semester of that course

with another group while taking the second semester. I also had to

complete a course in public speaking — required only for EE

students, as Prof. Ames stoutly maintained that an engineer should be

able to speak publicly. Although I thought it a complete waste of my

valuable time, I had no choice but to take the course. As I look back

on it, that course had greater benefit for me in later life than any

other college course I ever took! Although my cadet and National

Guard training had taught me to speak to groups of people, making

formal public speeches was something I had done only once in my life

— at church many years before. Each of us in the class had to

make three speeches during the semester, one of which was to be

humorous. One of the students spoke on the three queens of burlesque,

and "brought the house down." Thus I was emboldened to

speak on "The Engineer Selects a Wife," which went over

quite well. I have often wondered since if some of the best years of

my life would have been so good had I not had that preparation in

public speaking.

Both

my younger sister and my younger wife (see left) had graduated

from college, and it was now my turn. My attendance at the Coast

Artillery School the preceding autumn had prevented me from taking an

essential EE lab course, but the EE prof, Norman Bruce Ames,

graciously allowed me to attend the first semester of that course

with another group while taking the second semester. I also had to

complete a course in public speaking — required only for EE

students, as Prof. Ames stoutly maintained that an engineer should be

able to speak publicly. Although I thought it a complete waste of my

valuable time, I had no choice but to take the course. As I look back

on it, that course had greater benefit for me in later life than any

other college course I ever took! Although my cadet and National

Guard training had taught me to speak to groups of people, making

formal public speeches was something I had done only once in my life

— at church many years before. Each of us in the class had to

make three speeches during the semester, one of which was to be

humorous. One of the students spoke on the three queens of burlesque,

and "brought the house down." Thus I was emboldened to

speak on "The Engineer Selects a Wife," which went over

quite well. I have often wondered since if some of the best years of

my life would have been so good had I not had that preparation in

public speaking. Those

bars became a reality early in 1939, and I was given command of

Battery E, formerly "belonging" to now-Major Bullis. This

was my first experience with automatic weapons, and it was a little

awkward to learn from the top! Even before the promotion came, I had

another training course opportunity, this time at Fort Meade, just a

few miles away in Maryland. Here I was introduced to map warfare, as

we students re-fought on maps some of the Civil War battles. At the

conclusion of the course I was given a certificate of capacity as

major, and I hadn’t even made captain yet! My only recollection

of these two weeks was a lunch at the officer’s club. I was

staying at Mother’s house in nearby Hyattsville, but even so

had to leave at six-thirty in the morning to get to class by eight.

So by lunch-time I was starving. This day the no-options menu was

liver and turnips, the one meat and one vegetable I thoroughly

detested — but I ate them.

Those

bars became a reality early in 1939, and I was given command of

Battery E, formerly "belonging" to now-Major Bullis. This

was my first experience with automatic weapons, and it was a little

awkward to learn from the top! Even before the promotion came, I had

another training course opportunity, this time at Fort Meade, just a

few miles away in Maryland. Here I was introduced to map warfare, as

we students re-fought on maps some of the Civil War battles. At the

conclusion of the course I was given a certificate of capacity as

major, and I hadn’t even made captain yet! My only recollection

of these two weeks was a lunch at the officer’s club. I was

staying at Mother’s house in nearby Hyattsville, but even so

had to leave at six-thirty in the morning to get to class by eight.

So by lunch-time I was starving. This day the no-options menu was

liver and turnips, the one meat and one vegetable I thoroughly

detested — but I ate them.

The

major family event of 1940 was Mary Jo’s marriage to Clyde

Balch (see left) on April 14, 1940. It was held in our church

of the time, Gunton-Temple Presbyterian, on 16th Street (as earlier

mentioned). I don’t have a wedding picture, but this is a good

one of the couple. The wedding must have drawn a family gathering, as

the picture to the right shows (left to right) Marion with Bobby

Caruthers in front of her, Uncle Wilbur holding Lynne Caruthers, Mary

Charlotte, Margaret, Mother and Dad (with Bob Caruthers in the

background).

The

major family event of 1940 was Mary Jo’s marriage to Clyde

Balch (see left) on April 14, 1940. It was held in our church

of the time, Gunton-Temple Presbyterian, on 16th Street (as earlier

mentioned). I don’t have a wedding picture, but this is a good

one of the couple. The wedding must have drawn a family gathering, as

the picture to the right shows (left to right) Marion with Bobby

Caruthers in front of her, Uncle Wilbur holding Lynne Caruthers, Mary

Charlotte, Margaret, Mother and Dad (with Bob Caruthers in the

background).