GRADUATE STUDENT AT HARVARD

“Gangplank” Promotion

Although

I was released from active duty in early November 1945, my nearly

five years service entitled me to terminal leave until February

16,1946, so I didn’t have to find a job immediately. After

selling our house in San Bernardino, we headed East, visiting Mrs.

Chapman in Newport News and settling in with Mother in Hyattsville. I

wanted to return to the Government Printing Office, in order to make

sure my war service would be considered a part of my service there,

and because I needed something to do. It didn’t take me long to

get back my speed of operation, and to pick up the details of the

job. The Printer’s Union dues had been paid for all of us in

service by our local all the time we were gone, so my status as a

union operator was preserved. I didn’t realize then how

valuable that was to be for me in just a few months. The newspapers

published a plan adopted by the Administration to reward the

demobilizing veterans with ‘gangplank promotions', provided

they had accumulated sufficient time in their last war-time grade. My

calculations showed that I just barely qualified for promotion to

full colonel, so I eagerly watched the mail for the notice to come.

In January I got impatient and wrote a letter of inquiry to my

separation center. They responded with the coveted special order,

which had to be rescinded when the one that was already in the mill

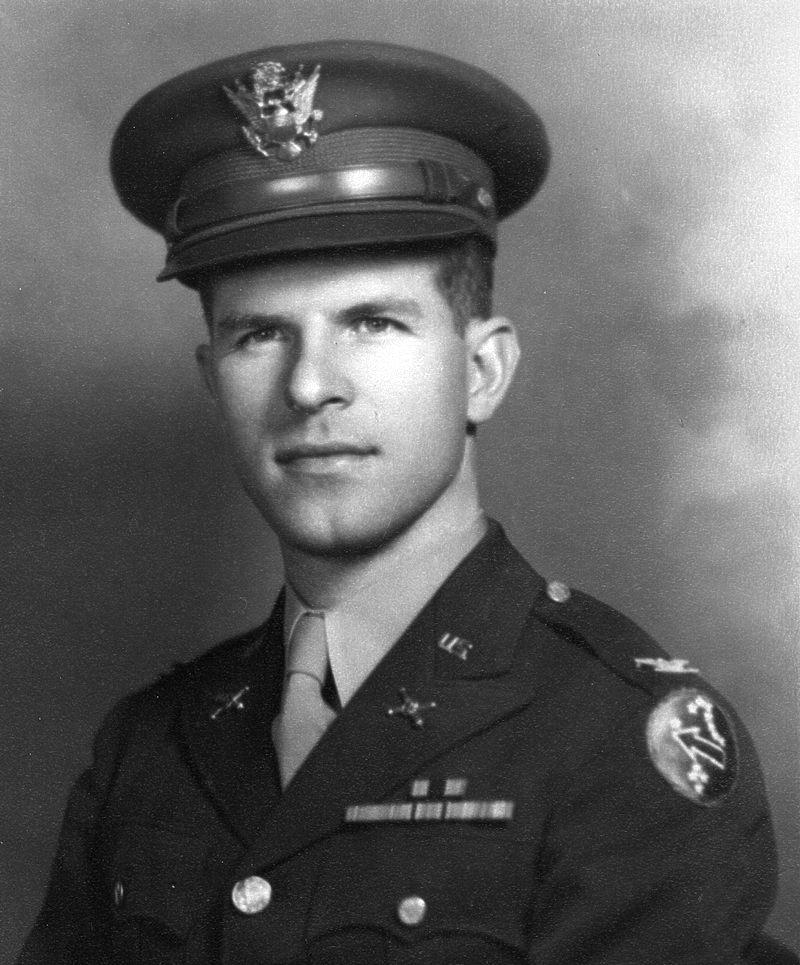

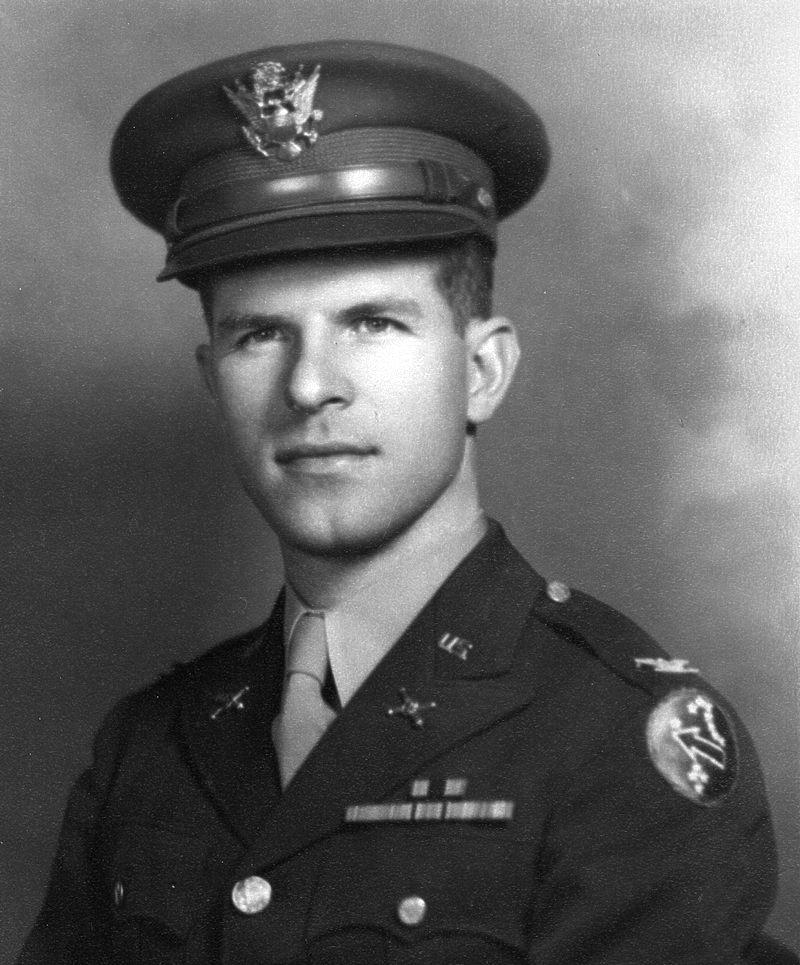

came out, as I couldn’t be promoted twice! I could now wear

eagles on my shoulders (see above left), and could hardly wait

to sport them in front of my uncle, Dr. Wilbur Phelps (my mother’s

brother), who had earned his eagles in World War I.

Although

I was released from active duty in early November 1945, my nearly

five years service entitled me to terminal leave until February

16,1946, so I didn’t have to find a job immediately. After

selling our house in San Bernardino, we headed East, visiting Mrs.

Chapman in Newport News and settling in with Mother in Hyattsville. I

wanted to return to the Government Printing Office, in order to make

sure my war service would be considered a part of my service there,

and because I needed something to do. It didn’t take me long to

get back my speed of operation, and to pick up the details of the

job. The Printer’s Union dues had been paid for all of us in

service by our local all the time we were gone, so my status as a

union operator was preserved. I didn’t realize then how

valuable that was to be for me in just a few months. The newspapers

published a plan adopted by the Administration to reward the

demobilizing veterans with ‘gangplank promotions', provided

they had accumulated sufficient time in their last war-time grade. My

calculations showed that I just barely qualified for promotion to

full colonel, so I eagerly watched the mail for the notice to come.

In January I got impatient and wrote a letter of inquiry to my

separation center. They responded with the coveted special order,

which had to be rescinded when the one that was already in the mill

came out, as I couldn’t be promoted twice! I could now wear

eagles on my shoulders (see above left), and could hardly wait

to sport them in front of my uncle, Dr. Wilbur Phelps (my mother’s

brother), who had earned his eagles in World War I.

My

involvement with radar and gun-laying directors had convinced me that

I wanted to enter the new field of electronics, but needed to qualify

as an expert by getting a PhD at a university specializing in that

field. Not knowing where that might he, I solicited the advice of my

professors at George Washington, Prof Ames (EE) and Dr. Brown

(Physics). To my surprise they independently recommended Harvard

University, and offered to write testimonial letters for me. I'm sure

those letters were instrumental in my being accepted, as Harvard was

receiving three to four times as many applicants as could be

accommodated. Acceptance was received shortly after the first of the

year, and I was able to arrange my resignation from the GPO and head

for Boston with our little family before the end of January. I can

still remember the frozen streets and snow-piled yards of the houses

we passed. We didn’t see the ground until April.

We Become New-Englanders

Post-war Boston was crowded.

Finding a place to live was difficult. Fortunately we had a car, so

could chase down the few ads for houses for sale and rooms to be

rented. We found a two-family house for sale in Brighton (which we

bought with our VA guarantee and no down payment), but were dismayed

to learn that we would have to wait up to three months for the renter

to relocate. Fortunately for us, the upstairs family had no children,

as the downstairs family did, and they moved out within the three

months allotted. Meanwhile, Mary Charlotte and I had to rent a room

in a row house owned by an Irish lady named Mrs. Frame on Green

Street, Jamaica Plain, in the southern section of the city. Boston

had a fairly good subway system, so getting to Harvard and downtown

to work was not too time-consuming. But living in one bedroom, eating

all meals in the crummy local restaurants, and having to farm out our

children did not make for joyous living. From an ad in the paper, we

located a family named Baker in one of the northern suburbs who took

Will and Mary Francis. Even after we had moved into our (second

floor) home, we decided to leave them with the Bakers, as I had to

work at night and sleep in the daytime. The original three months

stretched to over two years before we were able to have the kids with

us again.

My First Year at Harvard

I plunged into

my studies with much gusto, taking five subjects (the normal was

four), and even audited a sixth. When my last Army check had been

spent, I realized that I would have to work. The GI Bill which

Congress had just enacted provided for all my University expenses,

even including books, and $90 a month living costs as well, but that

didn’t even pay for the children’s care. My union card

was a passport to a job, however, and I was first sent to the Rapid

Service Press which had four linotype machines and needed a part-time

night operator. Pay was only $1.35 an hour, the frozen war rate, but

union negotiations had already provided for doubling that, which I

received in due time. I was able to phase my class days and my work

nights to allow an average of six or so hours sleep a night but study

time was hard to come by. One of my courses was electronics lab. The

university had acquired three SCR-584 radar units from the Marine

Corps, and assigned them to our class. We formed teams to study these

units, and physically adjust and align all their circuits, proving

our work by actually tracking airplanes. Having had that excellent

course on these complex devices at the AA School just two years

earlier gave me a real advantage over the other students, and our

team was the only one to get its 584 to track a plane.

Near

the end of the first semester, the school notified me that I would

have to find a professor to sponsor my PhD research, if I wanted to

pursue that degree. The German V2 bomb had shown that space was now

open to man, so I thought a good subject would be the design of an

instrument for spatial navigation. I started out to interview each of

the seven professors in the Department of Engineering Science and

Applied Physics (ESAP) of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

One after another, they all turned me down. Finally I was sent to Dr.

Howard Aiken, a tall, austere man, who upon hearing my proposal

answered, "I am not interested in that; but if you want to study

the application of this computer to the social sciences, I’ll

sponsor your research." The only thing I heard him say was "I’ll

sponsor your research." In my entire university career I had

taken only one social science course, economics. "This computer"

turned out to be Mark I, a monster machine Aiken had designed and IBM

engineers had built for Harvard for which Aiken was pictured on the

cover of Time magazine as the "father of the automatic computer"

some months later. Upon my immediate assent, Prof. Aiken turned me

over to Grace Hopper, one of the two or three programmers assigned to

the Computation Laboratory. She provided me with some reading

material on the machine, and I spent as much time as I could during

the summer months learning how to program this computer.

I

took three more courses during the summer term, qualifying for the MA

degree in electronics. The extra work at Rapid Service Press dried

up, so I shifted to the newspapers, first the Boston Herald, and then

the Boston Globe. Several factors were in my favor: (1) The end of

price control and rationing had released the stores to offer

merchandise long in short supply, and they were making a mint,

advertising more and more; (2) the newspaper had to hire whomever the

union endorsed as qualified; and (3) the regular journeymen had to

hire substitutes as available to "burn" up their overtime

hours, a union requirement. Thus I was able to get as much work as I

wanted, and on almost any night I wanted. All I had to do was to turn

my name-slug to show my name, and some regular would put it on the

time-board in place of his own, signifying that I was to work his

shift, and receive his pay. When I didn’t want to work, I kept

my name-slug turned to the blank side. Since everything was done by

seniority, I soon worked my way up to the top of the sub board. When

this happened, I was eligible to be hired as a regular, and this

happened early in 1947.

Mary Charlotte wanted to work, and

plenty of work was available. She first tried a laundry clerk

position, but soon gave that up, as she didn’t like to handle

the filthy clothing that was brought in. Then she tried assembling

hearing aids, and later making rubber boots. In both cases, the firms

offered high wages to trainees, but as soon as their training time

was over, their pay was piece-work. Not being very fast at the work,

Mary Charlotte’s pay dropped to less than half as soon as her

training time was over, so she quit. Eventually she got a job in the

Harvard Widener Library, and kept it for the rest of my time as

student there.

We saw the children every week-end, either

visiting them at the Bakers, or bringing them to our home in Brighton

for a few hours. We also attended church in nearby Brookline, when

permitted by a rare non-working Saturday night. Week-ends were my

only opportunity to catch up on my sleep, often only four hours per

24, and to do the many assignments my courses required. Mary

Charlotte would prepare a set of snacks for me and place them at my

elbow as I was working on my assignments. I would eat the snacks

without even knowing it! I also did a lot of reading on the subway

between Brighton and Cambridge. We sold our car, as I had decided I

couldn’t afford the compulsory insurance, which had the highest

cost in the entire country. Ironically, our home in Brighton (part of

the city of Boston) was just a block from Brookline, in which the

insurance rate was less than half that for Boston.

Second Academic Year

During the autumn of 1946, I had

two course credits entitled "research time." This work was

programming the Mark I. Dr. Aiken had decided that my research should

be a major computation needed by one of the University economics

professors, Wassily Leontief, who became a member of my doctoral

committee. Dr. Leontief was pioneering an economic theory entitled

"Input-output", which essentially said that the economy of

a country could be subdivided into interdependent sectors. If the

dollar amount of goods and services passing between one sector and

each of the others could be determined, it would be possible to

calculate the increase in performance of each sector needed to meet

some national goal, such as a war effort, a building boom, or any

other major change desired in the levels of production. The

calculations required, however, were completely beyond the

capabilities of then existing calculating machines, and that is why

Dr. Aiken wanted me to figure out how to get his new computer to do

the job. I started out with a model of a 10-sector economy, for which

I had to find the levels of production for each sector for a

hypothetical national goal. Mathematically speaking, this entailed

the specific solution of a 10x10 matrix. A full matrix of that size

had never before been calculated. The engineers had just finished

installing a new set of hardware devices, called subsequence units

(ten of them). I made use of them to solve this problem, as well as

to enable the engineers to check out their work. It took Mark I about

24 hours to finish the calculation (after I finally got all the bugs

out of the program), using just about every register and calculating

unit it had. Aiken and Leontief were delighted. Incidentally, it was

about this time that a malfunction in the computer was discovered to

have been caused by a moth getting into a relay — hence the

term "bugs" in a computer or program. Grace Hopper helped

me with a number of problems in setting up the program, and I was

grateful for her help and suggestions.

A real financial blow

came in January 1947, when the Veterans Administration terminated my

$90 a month living allowance, and demanded my return of that

allowance for the past five months! Because of some abuses of the GI

Bill, Congress had passed an amendment denying living allowance to

persons receiving pay for their schooling. The language was vague,

however, and the VA representative at Harvard assured me that I would

not be affected. However, when I had to submit a form on which to

show any employment, the bureaucrats decided that I was affected, and

was not entitled to the allowance from the date of the change. Since

I had been working just enough to make ends meet, I told the VA man I

could not repay the $450. Two months later, I received word that I

had been eligible for a dividend from my GI insurance, but the VA had

taken it to satisfy my debt to them. The amount of the dividend?

$450! This loss of income required me to increase my hours of work

and to accept the full-time job when offered.

Full-Time Study—Full-Time Job

Work as a linotype operator at the Boston Globe

was an experience in itself. The machines were crowded into a corner

of the top floor of the newspaper building, which must have been

fifty years old. We composed nearly all the reading matter printed,

including that in many of the ads. The classifieds, the neighborhood

movie ads, and the sports columns constituted most of my work. I soon

knew every movie being shown and every actor in each of them, often

having to correct the erroneous copy. I got to know the name of every

horse on every track in the country, and every player of the

baseball, football, soccer, basketball, curling, and you-name-it

sports in eastern USA and Canada. My interest in sports has been zero

ever since! Ever so often we had to do the "Set and Kill."

Where the advertiser supplied his own matrix for the ad, union

regulations required that the operators set up the reading matter in

those ads, even though it was not to be printed. Many times the

volume of work was more than we could get done in the regular shift,

and we would have overtime — one, two, or four hours. If this

was the beginning of a school day, this time came right out of my

sleeping time. The overtime pay, however, enabled me to cut back on

total work hours, so I welcomed it.

When told I would have to

take the full-time job or go to the bottom of the sub-board, I

decided that I had better take it. I had classes on Monday,

Wednesday, and Friday mornings, with computer lab work in the

afternoons. If I could get the night shift which gave me Sundays and

Thursdays off, I would have only one night a week with a short

sleeping time. The foreman said he didn’t think I could have

it, as shift assignment was by seniority, but I did get it, and that

enabled me to survive that very full semester at school and still

work nearly full time (I had to put on a sub when over-time hours

accumulated). The full-time job also provided hospitalization

insurance coverage for my family and me, so Mary Charlotte and I

decided that Will and Mary Francis should have their tonsils taken

out. When we told them they were going to the hospital, they were all

excited and eagerly looked forward to it. We felt like hypocrites

when we visited them immediately after the operation, as they had the

longest faces we had ever seen on them.

I managed to wrap up

all the course requirements for my PhD by the end of the spring term

of 1947, leaving only my thesis, my oral exams, and my language

qualification tests to be completed during the next school year.

However, I just squeaked by in the course in Applied Mathematics —

a major course taught by a French import, Dr. Brillouin. This man had

developed a theory of integration called the saddle-point theory, by

which one could integrate mathematical expressions not otherwise

possible. He had dwelt on this theory in class, but no one expected

him to make it the sole part of the final examination. He gave us

four formulas to integrate by this method, right out of the back of a

mathematics handbook. I got the first one done in one hour. The

second I bogged down on after five minutes, so put it aside. The

third took another hour, as did the fourth, allowing me just enough

time to finish it before time was called. There was a fifth question

from Dr. Aiken, on a lecture he had given which I had not attended,

due to overtime work, and which I had overlooked in studying my notes

from another student. I went home, read my notes and worked the

bypassed problem and Dr. Aiken’s problem in an hour each. Three

out of five gave me 60% — hardly a passing grade. This exam was

the only measure of competence, and a grade less than B in one’s

major field meant OUT, no second chance. I had just about given up

all hope of getting my doctorate, when the grades were distributed; I

got a B-! Praise the Lord! I learned how it happened just by chance

(?) several months later when Dr. Aiken was talking about the

examination to someone else. It seems that Dr. Brillouin was called

back to France for a consultation, and had Dr. Aiken mark the papers.

As I recall his words he said, "One guy got 100, the next was

80, and the grades ranged from there down to 10. I decided to accept

60 as passing." I have wondered since if my being his only

research student had any bearing on his decision. Without any extra

effort on my part other than to apply for it, I was awarded a new

degree, along with seven others, called Master of Engineering

Science. I believe it was instituted to provide a recognition for two

years’ graduate work when a PhD was not obtained. The degree

was discontinued two years later.

Even with all the pressure

of school and work, I had not neglected my military career. Since I

was already in Boston when my terminal leave expired (when I reverted

to inactive status), I quickly affiliated with an Active Reserve unit

there. I attended a few of its meetings, hoping to learn something

about the rocket principle behind the German V-2 rocket bombs.

Instead I was assigned to give a lecture on the subject, and had to

dig the principle out for myself. Opportunity for a refresher course

for officers, to be held at Fort Benning GA in June, was just down my

alley, and I applied and was accepted. Those two weeks have

contributed to my military pension for over 32 years now.

Third Academic Year

Although I had no formal courses during the

summer, I found it expedient to spend a good deal of time at the

Computation Lab. Dr. Aiken and Dr. Leontief had decided that my

thesis subject was to be the inversion of a matrix of order 38. What

this means is that my thesis would be the result of programming and

computing the general solution to a set of 38 simultaneous linear

equations, each representing the annual contribution of one of the

sectors of the US economy to the other 37 sectors. The term "general"

meant that my computation would generate the coefficients of the 38

unknowns in each equation which, when any set of specific values of

the outputs was given, the unknowns (each representing needed

production of one sector) could be calculated. Dr. Aiken and his

hardware staff had been deeply involved in developing a new computer,

to be known as Mark II, more than ten times faster than Mark I, and

my computation would be used as the guinea pig to check out the

hardware of this computer. Mark II was actually two identical relay

computers, with a check register that continuously compared the

results from each unit, stopping computation instantly if a

disagreement was detected in the two values. Dr. Leontief and his

colleagues at the University had put in an enormous amount of work in

generating the numbers they supplied me, representing the 38x38

"inputs" to our national economy. I knew nothing of that

work or even the theories on which it was based. I just took the

numbers and carefully punched them into paper tape to be used as

input for my program. Although the decisions were made during the

summer, construction of the computer was slow, and I didn’t get

down to the initial checking of my programs until well into the

autumn, and actual computation did not begin until January

1948.

Meanwhile Dr. Aiken decided that I should teach a

laboratory course on computation and programming, as part of my

training for the doctorate. So Harvard hired me as a lab instructor

at $180 per month. They only paid me $125, however, as that was the

most a veteran could earn and still get his living allowance of $90.

The bureaucrats were most unhappy to learn that I got no living

allowance, and that they would have to pay me the full $180. This lab

course took a great deal of my time, but it was worthwhile. For the

first semester’s work, Dr. Aiken had obtained about 50 old

Marchant calculators, on which my students had to work out by hand

the solution to a variety of mathematical problems. One poor student

just could not get the right numbers into the machine, and he took

two to three times as much time on the course as the others. The

second semester was devoted to the programming and running on Mark I

of a series of small programs. I believe that was the very first

programming course ever conducted in the US. Not having classes to

attend in the morning (the lab work was all in the afternoon), my

sleeping hours were much more reasonable. However, all my time on the

Mark II had to be done at night, as the engineers had the machine

every day. This competed with my work at the Boston Globe, but I

managed to get enough work to pay our bills. Just before Christmas, a

notice was given at the Reserve Officers meeting of a 2-month

opportunity for a qualified Reserve Officer to be Assistant PMS&T

(professor of military science and tactics) at Boston College —

in AA gun gunnery. I applied for the job and was interviewed by the

Regular Army colonel who was the PMS&T, but did not know AA

gunnery. He objected to my service as almost exclusively automatic

weapons, until I pointed to my superior rating at an AA gun gunnery

course I had taken in Hawaii while waiting to come home, and to my

radar course. I got the job, and became the second Protestant on the

staff of this Roman Catholic institution. Now I had three full-time

jobs — student, linotype operator, and professor. My seniority

at the Globe had caused me to be transferred to the Day Side (better

hours, same pay), which I could not handle, so I had put a sub on and

left him there. On my next visit to work the one day a month I had to

work to maintain my active status in the union, the union secretary

told me I would either have to give up my regular job or come to

work. I gave up the job.

My Thesis Computation

Finally Mark II was ready for my

computation. There was no internal or disk memory in these early

computers. All data had to be fed in from punched paper tape at 10

characters per second (modern computers operate at millions of

characters per second), and intermediate values had to be punched out

on paper tape and then read back in when needed. I had already

punched up the primary data tapes with the 1,444 industry

input-output values on them, and also the program tape. In addition

to the 38 columns of numbers in each of the 38 rows, I used a 39th

column (originally the sum of the 38) as a check column, receiving

the same operations as each of the 38. The computer compared this

check value when reached with the running sum of the preceding 38

values to insure that there was equality. Any discrepancy signaled an

error. About 10% into the calculation, the computer fouled up on the

current check number, and we had to compute it by hand before

continuing the main computation. As I had to go to work at the time,

Art Katz (a student friend) calculated it for me, and got the Mark II

back into operation. Three weeks later I got a phone call while at

the Globe from the chief engineer saying that the check number had

"blown up" and would I come to the Computation Lab to take

care of it. There were at the time 12 bushel baskets full of paper

tape rolls. Which one of the thousands of numbers was responsible?

The thought came to me [from God?] that perhaps Art had made an error

in computing that check number three weeks earlier. I immediately set

about to recompute that value. It took me all day, but I got it done

just before the night shift of engineers came on duty. The next day

brought the confirmation that the new number was okay, and the

computation ran to completion — taking only six weeks! The

chief engineer, who had hardly looked at me before, now thought I was

a genius, as he thought we would surely have to start all over

again.

The final values had to be typed up by hand and

presented to Dr. Leontief. Twenty-five years later he would be

awarded a Nobel prize for this and subsequent work in Input-Output

Theory. The inverse could readily be proved by multiplying itself by

the input matrix, which should give the unit matrix, just as

multiplying any number by its inverse gives one. The result showed a

precision (accuracy) of our numbers to over 9 decimal places. Unknown

to me, one of the Nation’s foremost mathematicians, Dr. John

von Neumann, had been wrestling with the theoretical considerations

of the very calculation I had undertaken. He published his results in

the Journal of the American Mathematical Society early in 1948. Using

very involved advanced mathematical concepts, he had come to the

conclusion that the accumulated round-off error in a computation of a

matrix inversion of any large magnitude would greatly erode the

accuracy of the results. (Round-off error is experienced when the

full span of digits obtained from multiplication, which is the sum of

the digits in the inputs to the multiplication, is truncated to the

number of places carried by the computer.) An even greater hazard in

this particular type of computation is the loss of precision when two

nearly equal values are differenced, particularly if the resulting

difference is used as a divisor. Since this sequence of steps is an

integral part of the matrix inversion process, the loss of accuracy

could be catastrophic. In a table in the appendix to his paper, Dr.

von Neumann estimated that in the inversion of a 38x38 matrix with a

computer carrying ten-place values (my situation), the results could

be depended on for only three places of the ten. When my work was

completed, it tested correct to over nine places of the possible ten!

Dr. Aiken was so pleased to be able to refute the great von Neumann

that he strongly recommended I be granted my degree. Without that

incentive, I might still be at Harvard trying to produce something

sufficiently unique and worthwhile to be rewarded with a PhD from

Harvard.

Orals and Language Qualification

With the thesis work done, I dug into the task of

preparing the thesis document itself, which occupied most of March

and April. I also had to pass my orals and the two language

competence tests (French and German). Since the degree requirements

involved one major field (in my case numerical analysis) and three

minor fields (I chose antennas, vacuum tubes, and traveling wave

tubes), my orals covered all these fields. Prof. Mimno gave me the

hardest time, in his questions on traveling wave tubes, in which he

was the University expert. I had had only one course in them (under

him), and was by no means an expert. His questions got more and more

specific, and I was struggling to describe the phenomena in terms of

voltage changes until I realized that I was over my depth, and

thought, "This is the end." Almost as an afterthought [from

God?] in the last answer I said, "Of course, one can describe

these phenomena in terms of current variations also." He stopped

at once. That was what he had been trying to get me to say.

The

language tests brought on another miracle. The German test was tough,

but I was reasonably well prepared for it, with my background of

Scientific German at George Washington Univ. The French was something

else. The secretary of the Computation Lab had been a French major,

and she had had great difficulty in passing the test there at

Harvard. When she learned of my pitifully weak background in French,

she was aghast, and urged me to spend full time boning up for the

exam. That was impossible, as I was up to my ears in completing the

thesis and handling my lab students. When the date for the French

exam was posted, it conflicted with my lab class. I asked Dr. Aiken

what I should do, and he said he would arrange for me to take a

make-up, which he did. The make-up test was "duck-soup", a

paragraph from a French mathematics paper that anyone knowing the

math could have understood, even if he never studied French. That

hurdle was passed! Praise the Lord, who most certainly must have

arranged it.

Dr. Herbert F. Mitchell, PhD

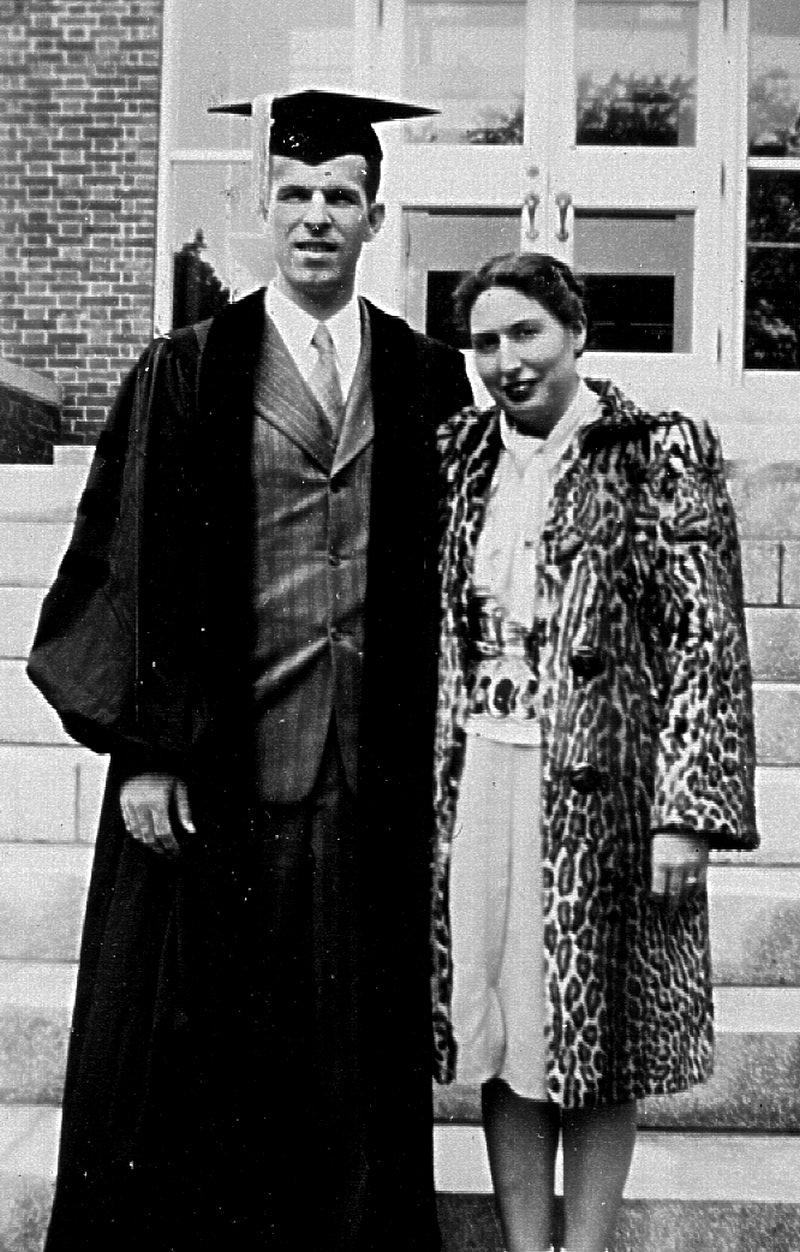

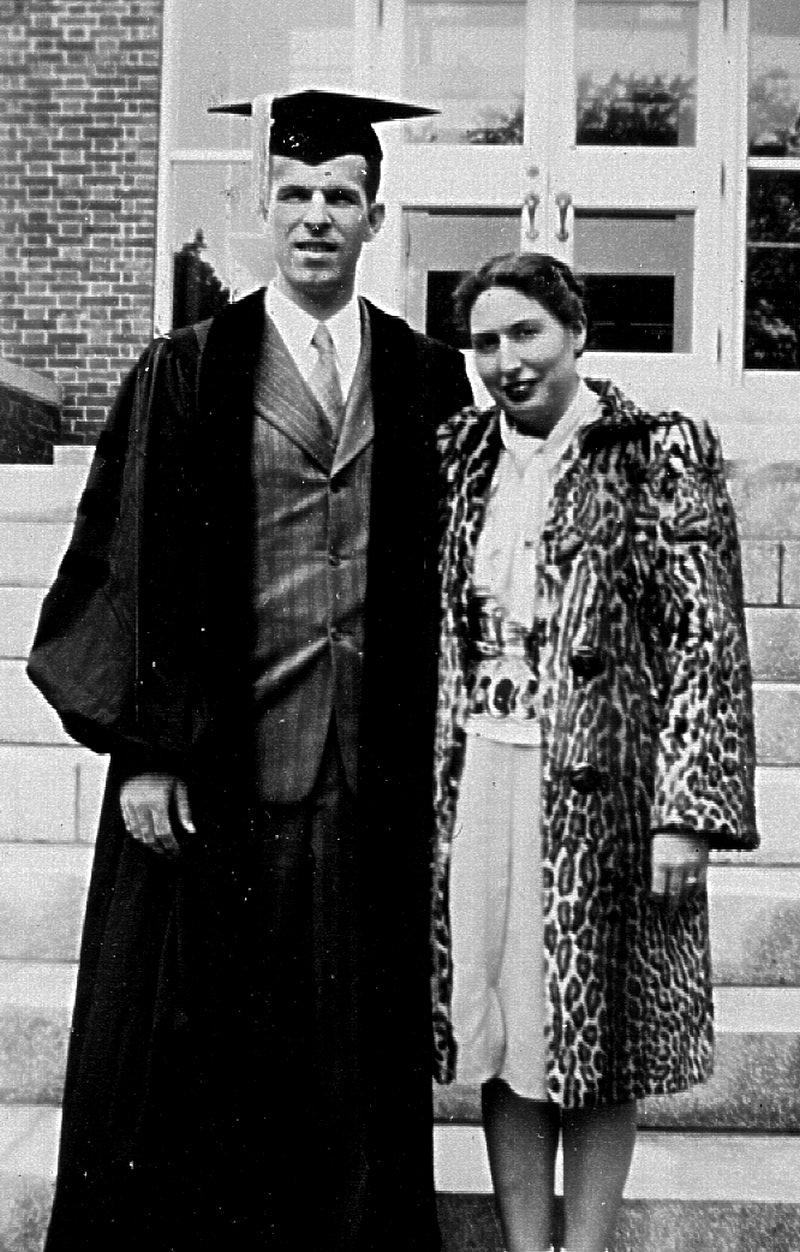

Commencement

exercises were scheduled for the morning of June 11th, 1948, with an

address at the Harvard Club in the afternoon by General Marshall, now

Secretary of State. Mother, Dad, Marion, and Mrs. Chapman had flown

up from Washington to observe the ceremony. Mary Charlotte and I had

driven up from Glen Cove, Long Island, where I had already started on

my new job as professor of engineering at the Webb Institute of Naval

Architecture. Each graduate had two tickets for General Marshall's

address, and as Mary Charlotte was anxious to get back to Glen Cove, I

gave my tickets to Mother and Marion. I didn't know then that history

was in the making, as that was where the famous Marshall Plan for

Europe's recovery from World War II was unveiled. As I drove out of

Harvard Yard, I realized that another page in my life had been

turned. Henceforth I would be addressed as DOCTOR Mitchell.

Commencement

exercises were scheduled for the morning of June 11th, 1948, with an

address at the Harvard Club in the afternoon by General Marshall, now

Secretary of State. Mother, Dad, Marion, and Mrs. Chapman had flown

up from Washington to observe the ceremony. Mary Charlotte and I had

driven up from Glen Cove, Long Island, where I had already started on

my new job as professor of engineering at the Webb Institute of Naval

Architecture. Each graduate had two tickets for General Marshall's

address, and as Mary Charlotte was anxious to get back to Glen Cove, I

gave my tickets to Mother and Marion. I didn't know then that history

was in the making, as that was where the famous Marshall Plan for

Europe's recovery from World War II was unveiled. As I drove out of

Harvard Yard, I realized that another page in my life had been

turned. Henceforth I would be addressed as DOCTOR Mitchell.

Reflections

I cannot pass by this period in my life without acknowledging

God’s omnipotence in controlling all factors of a complex

situation. This whole episode was one miracle after another. First,

the choice of Harvard was completely outside my control. Even with my

acceptance, how is it that Mary Charlotte, who had never before or

since been willing to live in New England, was willing to go there at

this time? Next, my acceptance when only one in three or four was

admitted must have been a work of God Himself. Third, our support was

never lacking, with income from the VA, from the printing trade, from

the Army, from Mary Charlotte’s earnings, and finally from the

University enough to meet our needs. We did not borrow throughout all

this time. Fourth, the choice of my PhD research was completely the

Lord’s — I did not know who Dr. Aiken was. I had never

heard of his computer, and I certainly would never have chosen a

project from the social sciences if he had not made it mandatory. As

I look back on that incident and realize what that choice has meant

to me — it has affected every period of my life since — I

am overwhelmed with the realization that truly the Lord looks after

fools and the simple minded. Fifth, the simultaneous occurrence of my

need for access to a computer and the engineers’ need for a

guinea-pig computation to prove their work —- both on Mark I

and on Mark II — is still one more case of the Lord’s

orchestration. Sixth, the Lord’s guidance to the cause of the

blow-up in the computation at the half-way point was essential to the

successful completion of the work. It is problematical if I would

have been allowed the computer time to complete the calculation, if

it had been necessary to start over, as the engineers were through

with their check at about the same time as my problem was completed.

I could easily have spent several weeks trying to find the source of

that error — if I ever could find it — if the Lord had

not led me right to it. Seventh, my preparation for the oral

examination was inadequate — particularly in the three

collateral areas required for the doctorate, and I could easily have

been flunked out, particularly by Dr. Mimno, if the Lord had not

given me the inspiration to satisfy him. Eighth, my passing the

French examination was in some ways the greatest miracle of all, for

I made absolutely no preparation for it. If a text like any one of

the three presented on the German examination had been required, I

would have been hopelessly lost. Ninth, the passing of the course in

applied mathematics with only 60% on the final exam could only have

come about by Dr. Aiken’s substitution for Dr. Brillouin —

the latter would cheerfully have flunked two-thirds of the class! But

the greatest miracle of all was the concurrence of the publishing of

Dr. von Neumann’s study of the instability of the matrix

inversion calculation (essentially saying in a 125-page treatise in

the Journal of the American Mathematical Society that the calculation

on which I was engaged would almost certainly be riddled with

round-off error) with my results of almost complete accuracy. The

only reason for that accuracy was the tedious and careful compilation

of the industry coefficients for the input matrix by Dr. Leontief and

his coworkers. Had this computation been done in some other field, or

if the input data had not been so carefully and accurately compiled,

my results would have been as inaccurate as Dr. von Neumann’s

paper predicted. And I had absolutely nothing to do with these

factors. I was indeed the fool who rushed in where angels fear to

tread. Yes, although I had to work hard and faithfully for those

2-1/2 years, nevertheless my doctorate was a gift from the Lord

Himself.

Go to next

chapter

Return to Table of Contents

Although

I was released from active duty in early November 1945, my nearly

five years service entitled me to terminal leave until February

16,1946, so I didn’t have to find a job immediately. After

selling our house in San Bernardino, we headed East, visiting Mrs.

Chapman in Newport News and settling in with Mother in Hyattsville. I

wanted to return to the Government Printing Office, in order to make

sure my war service would be considered a part of my service there,

and because I needed something to do. It didn’t take me long to

get back my speed of operation, and to pick up the details of the

job. The Printer’s Union dues had been paid for all of us in

service by our local all the time we were gone, so my status as a

union operator was preserved. I didn’t realize then how

valuable that was to be for me in just a few months. The newspapers

published a plan adopted by the Administration to reward the

demobilizing veterans with ‘gangplank promotions', provided

they had accumulated sufficient time in their last war-time grade. My

calculations showed that I just barely qualified for promotion to

full colonel, so I eagerly watched the mail for the notice to come.

In January I got impatient and wrote a letter of inquiry to my

separation center. They responded with the coveted special order,

which had to be rescinded when the one that was already in the mill

came out, as I couldn’t be promoted twice! I could now wear

eagles on my shoulders (see above left), and could hardly wait

to sport them in front of my uncle, Dr. Wilbur Phelps (my mother’s

brother), who had earned his eagles in World War I.

Although

I was released from active duty in early November 1945, my nearly

five years service entitled me to terminal leave until February

16,1946, so I didn’t have to find a job immediately. After

selling our house in San Bernardino, we headed East, visiting Mrs.

Chapman in Newport News and settling in with Mother in Hyattsville. I

wanted to return to the Government Printing Office, in order to make

sure my war service would be considered a part of my service there,

and because I needed something to do. It didn’t take me long to

get back my speed of operation, and to pick up the details of the

job. The Printer’s Union dues had been paid for all of us in

service by our local all the time we were gone, so my status as a

union operator was preserved. I didn’t realize then how

valuable that was to be for me in just a few months. The newspapers

published a plan adopted by the Administration to reward the

demobilizing veterans with ‘gangplank promotions', provided

they had accumulated sufficient time in their last war-time grade. My

calculations showed that I just barely qualified for promotion to

full colonel, so I eagerly watched the mail for the notice to come.

In January I got impatient and wrote a letter of inquiry to my

separation center. They responded with the coveted special order,

which had to be rescinded when the one that was already in the mill

came out, as I couldn’t be promoted twice! I could now wear

eagles on my shoulders (see above left), and could hardly wait

to sport them in front of my uncle, Dr. Wilbur Phelps (my mother’s

brother), who had earned his eagles in World War I.

Commencement

exercises were scheduled for the morning of June 11th, 1948, with an

address at the Harvard Club in the afternoon by General Marshall, now

Secretary of State. Mother, Dad, Marion, and Mrs. Chapman had flown

up from Washington to observe the ceremony. Mary Charlotte and I had

driven up from Glen Cove, Long Island, where I had already started on

my new job as professor of engineering at the Webb Institute of Naval

Architecture. Each graduate had two tickets for General Marshall's

address, and as Mary Charlotte was anxious to get back to Glen Cove, I

gave my tickets to Mother and Marion. I didn't know then that history

was in the making, as that was where the famous Marshall Plan for

Europe's recovery from World War II was unveiled. As I drove out of

Harvard Yard, I realized that another page in my life had been

turned. Henceforth I would be addressed as DOCTOR Mitchell.

Commencement

exercises were scheduled for the morning of June 11th, 1948, with an

address at the Harvard Club in the afternoon by General Marshall, now

Secretary of State. Mother, Dad, Marion, and Mrs. Chapman had flown

up from Washington to observe the ceremony. Mary Charlotte and I had

driven up from Glen Cove, Long Island, where I had already started on

my new job as professor of engineering at the Webb Institute of Naval

Architecture. Each graduate had two tickets for General Marshall's

address, and as Mary Charlotte was anxious to get back to Glen Cove, I

gave my tickets to Mother and Marion. I didn't know then that history

was in the making, as that was where the famous Marshall Plan for

Europe's recovery from World War II was unveiled. As I drove out of

Harvard Yard, I realized that another page in my life had been

turned. Henceforth I would be addressed as DOCTOR Mitchell.